Today I read a very moving post on EverydayAspergers.com, a blog that helps raise

awareness about Asperger’s and females. The entire article really opened my eyes to my 17 year old daughter’s mental and emotional struggles as she tries to make her way in this world, yet feels the need to apologize every day for simply existing.

I was always bewildered by her low self-esteem, as I raised her with abundant compliments, unconditional love and unlimited support. I made it known to her that her voice and opinions MATTER and are validated.

Being raised in a very abusive and dysfunctional family setting myself, it makes sense to me why I struggled to overcome worthiness issues for so many years. But my beautiful, brilliant, quirky and ridiculously talented little girl faces similar obstacles, and after reading this I understand a little bit more about Asperger’s and the female brain.

Here are a few of the highlights that really stood out to me:

The times I need to curl in a corner and cry with the imaginary arms of someone around me, and then sobbing uncontrollably, as I realize like all the times before, there is no one there.

The truth of my isolation and how no one will ever be able to slip into my mind and understand.

Counting the minutes until I can sleep, hoping the sleep will help me escape the increasing thoughts of fear.

Realizing again and again I am different in a world that seems riddled with sameness. Understanding that the depths of me are so deep that even I get lost with no hope of escape.

Feeling like an alien. Feeling like an alien. Feeling like an alien.

The way in which I step back as observer and watch myself freak out and wig out and create chaos out of nothing, but still being unable to stop myself.

Thinking anything I say isn’t needed, is irrelevant, or will just bury me and leave me alone.

You can read her whole post here.

This prompted me to do some additional research on Asperger’s and suicide.

On the Spectrum News website I learned of a published study from The Lancet Psychiatry, revealing that two-thirds of a group of adults diagnosed with Asperger syndrome said they had thought about committing suicide at some point, and 35 percent had made specific plans or actually made an attempt.

35 percent!

For those with Asperger’s, struggling their whole lives to fit in can take a toll on them emotionally. Add to that autistic cognitive patterns such as the tendency to perseverate or get stuck on a particular line of thought and it can directly lead to vulnerability toward suicide.

What makes an Aspie teen a higher risk? AACC.net says the number one reason is social isolation and rejection. Aspies tend to have decent friendships in elementary school, but there is sudden shift in middle school.

Peers start noticing differences in behaviors; friends from elementary school suddenly distance themselves, which can be confusing (and terrifying) for the Aspie, who wonders why these people were friends in 5th grade but not in 6th.

Adolescence is a time students are seeking identity and peer approval. But odd mannerisms, avoiding eye contact, lack of filters for appropriate conversation, not understanding sarcasm or idioms, and constant interruption are just some of the things that cause an Aspie to be shunned or bullied as a teen. Increasingly harder schoolwork and being left out of group projects or teams can trigger anxiety and depression.

Tony Attwood, a clinical psychologist known world wide for his knowledge of Aspergers Syndrome, speaks about the Aspie tendency to catastrophize, making it challenging to regulate their emotions. Additionally, the amygdala of an Aspie tends to be 10-15 % larger than in neurotypicals, therefore inflating the “danger alerts” in the fight/flight/freeze system.

This means something that is a 1 on the scale of a neurotypical person may easily register as a 10 to an Aspie. As the brain sends signals that start the sympathetic nervous system racing, the person with Asperger’s may be the “last to know” about their heightened emotional state, making them just as surprised as an observer when emotions and behaviors have escalated.

How Can We Help?

The goal for crisis intervention is to increase the person’s sense of being emotionally supported as well as their psychological sense of possible choices.

Autism Help lists some the following strategies:

Establish rapport (e.g. ‘I’m listening and I want to support you’)

Explore the person’s perception of the crisis

Focus on the immediate past (e.g. a recent significant event or problem) and immediate future

Develop options and a plan of action

Increase the options available to the person and the number of people available to help

Try to involve appropriate people in the person’s natural support system

Encourage them to develop a plan including resources and support in the immediate future. Write down the steps of a personal safety plan and suggest the person carry them around for fast access to support.

Much like the Disaster Psychology module taught in CERT, you want to avoid certain phrases when communicating, such as, “Everything will be fine, don’t worry,” and “Come on, it isn’t that bad…” False reassurances, minimizing feelings, and intrusive questioning are inappropriate responses for individuals at risk for depression and suicide.

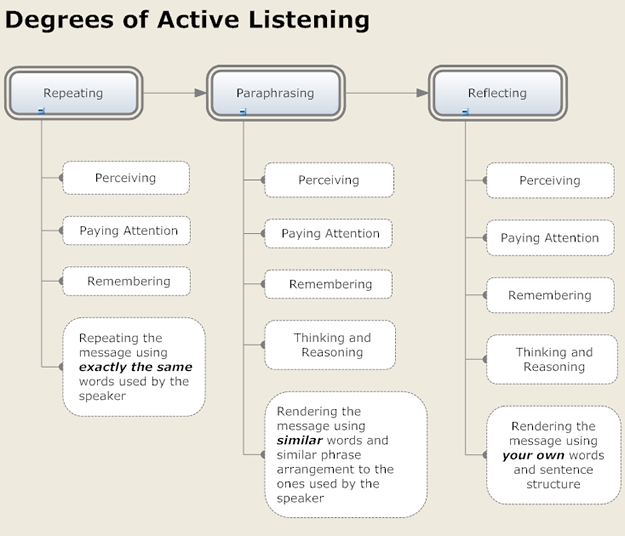

Instead, practice active and reflective listening techniques when the person shares their feelings with you and paraphrase and summarize often.

Repetitive behaviors such as spinning objects, opening and closing things repeatedly, rocking, arm-flapping, squealing, making loud noises or even hitting are common in those on the autism spectrum. Often ritualistic, they are known as perseveration or self-stimulatory behavior (stimming). While they may seem pointless and “weird” to us, they fulfill a very important function for the person carrying them out, such as relieving anxiety, counteracting and overwhelming sensory environment, regulating the nervous system or simply letting off steam. The frequency and severity of the behaviors varies from person to person.

Repetitive behaviors such as spinning objects, opening and closing things repeatedly, rocking, arm-flapping, squealing, making loud noises or even hitting are common in those on the autism spectrum. Often ritualistic, they are known as perseveration or self-stimulatory behavior (stimming). While they may seem pointless and “weird” to us, they fulfill a very important function for the person carrying them out, such as relieving anxiety, counteracting and overwhelming sensory environment, regulating the nervous system or simply letting off steam. The frequency and severity of the behaviors varies from person to person.