I’m 18. I graduated high school last July. I’m “high functioning” enough to be able to take care of my brother and myself when my mom is on night shift on the ambulance. I can dress myself (although not according to society’s “fashion” standards), I keep up with hygiene, sleep and wake on a self-imposed schedule, participate in online communities, cook for myself, help out around the house, and manage my own bank account. No, I haven’t learned how to drive yet. No, I haven’t applied for college. No, I don’t yet have a job but I’m looking for one. It really has to be something quiet and not too overwhelming, though, because there are currently no resources or tools for me to learn how to manage all the challenges I now face in the adult world.

I’m 18. I graduated high school last July. I’m “high functioning” enough to be able to take care of my brother and myself when my mom is on night shift on the ambulance. I can dress myself (although not according to society’s “fashion” standards), I keep up with hygiene, sleep and wake on a self-imposed schedule, participate in online communities, cook for myself, help out around the house, and manage my own bank account. No, I haven’t learned how to drive yet. No, I haven’t applied for college. No, I don’t yet have a job but I’m looking for one. It really has to be something quiet and not too overwhelming, though, because there are currently no resources or tools for me to learn how to manage all the challenges I now face in the adult world.

Autism awareness and diagnoses have risen dramatically… for young children. In elementary school my brother had access to all sorts of special accommodations and therapies. Unfortunately, being a girl, I actually didn’t receive a diagnosis until I was 17, because autism presents very differently in girls.

From infancy throughout the schooling years, interventions are readily available. But what happens when you turn 18? Where are the resources? Who teaches us how to interview for jobs? Buy a car without getting ripped off? Balance a checkbook? Pick the right auto insurance? Do taxes? Grocery shop and plan meals? Go on a date? Figure out the best cell phone plan? Find friends?

Society seems to think one magically “grows out of autism” once they reach adulthood, especially if you’re considered “high functioning.” My symptoms are seen as “not really severe” so I don’t qualify for any kind of adult support…

… yet I’m not entirely sure how qualified and ready I am to “adult” right now. Of course my mom works with me on some of these things, I don’t want to make it sound like she’s not parenting me and teaching me about life. But being a young adult with autism, trying to figure out the next steps to life presents with far more struggles than simple social skills deficits.

What is “High Functioning Autism?”

According to LoveToKnow.com, the term high functioning autism, or HFA, is used to describe individuals who meet the criteria for a diagnosis of autism, yet show no cognitive delays, and are able to speak, read, and write, as well as have IQ scores of average or above. Those with HFA do suffer difficulties in communication, language, and social interaction typical of autism, as well as repetitive behaviors and narrow interests associated with the disorder. Abstract language concepts, such as irony and humor may well be beyond the comprehension of adults with high functioning autism.

While with the right support we can manage independent and successful careers, marriages, and social lives, it can still be difficult to blend into the mainstream world. Crowds, even small ones, can activate sensory overload for me and make me shut down. Fluorescent lights, smells, or certain combinations of sounds make my nervous system crawl with pain and discomfort. I have extreme anxiety dealing with the public.

Social awkwardness and communication issues can make me highly misunderstood and even considered rude. Inability to maintain eye contact during conversation can cost a job interview or friendship, as it is often misinterpreted as dishonest or lacking interest. Maybe I pass an interview and secure a decent job, but the challenges don’t stop there. Workplace camaraderie is terra incognita for many high functioning autistic adults. Small talk and sarcastic humor go over my head, and I’ve been known to not have a filter when it comes to appropriate thoughts to verbalize in conversation. Don’t even get me started on not understanding body language or non-verbal cues and facial expressions.

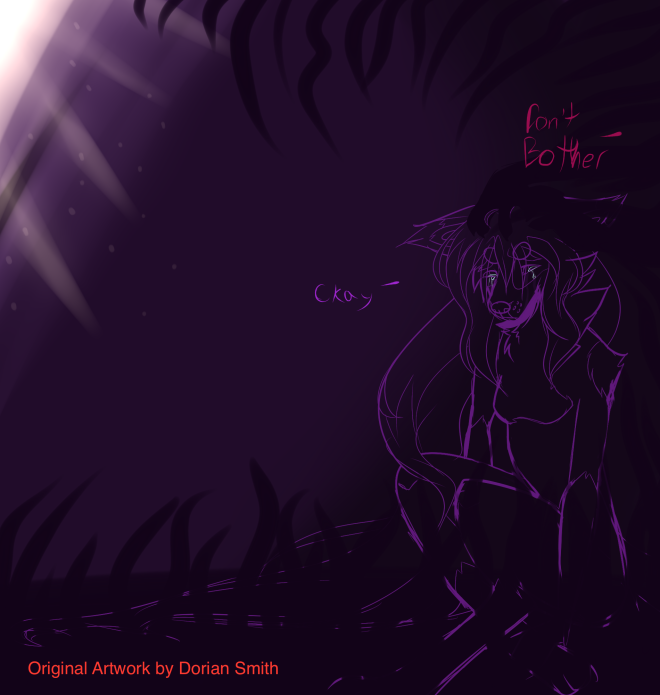

I’ve been accused of being odd, serious, quiet and aloof, when really I’m severely over-analyzing a simple response to “How are you?”

Being high functioning, I often feel that even the autism community discounts my struggles, as my deficits are compared to the hardships faced by the profoundly disabled. So I feel isolated from mainstream society, yet have trouble finding resources for my issues. Less severe symptoms mean I am denied applications for medical and psychological assistance.

I applaud all the awareness and resources put forth in general when it comes to autism, but there is a long road ahead of us still.

***

For tips on recognizing adults with autism on the scene of a crime, fire, medical call or disaster, check out this article, Trix Are for Kids, Autism is Not (Only)!